Rube Goldberg and Winning the Loser’s Game

Charles D. Ellis in his best-selling book Winning the Loser’s Game suggests that individual investors will be better off by working with the markets instead of against them. Based on historical facts he argues that investors need to avoid short-term traps to concentrate on their long-term strategies. The magic ingredients are time and compounding.

His advice has been echoed by Howard Marks, Jack Boggle, Warren Buffet and a host of other investment luminaries.

Their advice is simple, but not easy.

When I consider the behaviour of investors and the media, I sense the complete opposite. The focus on the short-term movements of the markets and the economy takes up so much of everybody’s limited time, energy and emotional headspace only to often lead to poor decisions and sub-optimal long-term outcomes. Most people seem to be long on strong opinions and short on humility.

The Rube Goldberg Affect

Rube Goldberg was an acclaimed cartoonist and inventor. He was a qualified engineer that turned to his love for drawing and became a cartoonist. He was known for his “invention drawings” of complicated machines which was a humorous critique of how industrialisation, intended to simplify our lives, could have the opposite effect. The machines that carry his name accomplish mundane tasks in over-elaborate ways — ideally with a sense of humour.

Rube Goldberg was an acclaimed cartoonist and inventor. He was a qualified engineer that turned to his love for drawing and became a cartoonist. He was known for his “invention drawings” of complicated machines which was a humorous critique of how industrialisation, intended to simplify our lives, could have the opposite effect. The machines that carry his name accomplish mundane tasks in over-elaborate ways — ideally with a sense of humour.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary even listed “Rube Goldberg” as an adjective, defining it as “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply.”

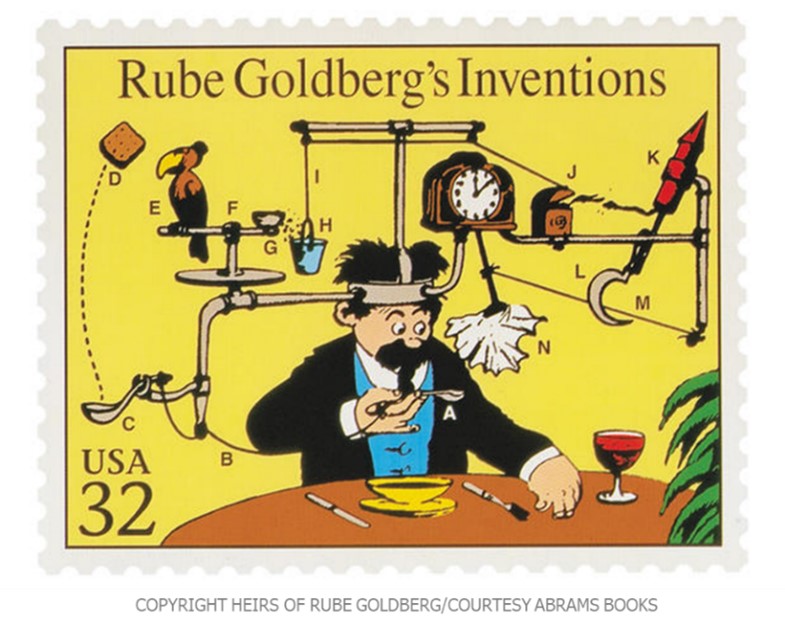

The machines were symbols, Goldberg wrote, of “man’s capacity for exerting maximum effort to accomplish minimal results.” He was a great artist who understood the modern world. In 1995 a US postage stamp honoured “Rube Goldberg Inventions” depicting his iconinc self-operating napkin.

A lot of the conversations in the media and financial services world feels Rube Goldbergian to me. It is a very complex environement I agree, but our job is to simplify complexity.

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s razor is a principle often attributed to 14th century friar William of Ockham that says that if you have two competing ideas to explain the same phenomenon, you should favour the simpler one as the most likely approximation of reality. It advocates simplicity by focusing on key elements of the problem, eliminating improbable options and finding solutions with less assumptions.

The simplest solution is usually the correct one.

This principle was academically tested in a study comparing simple vs complex forecasting methods. The research paper published in the Journal of Business research, “Simple vs Complex Forecasting: The Evidence” compared the findings of 32 academic papers and found that complexity increases forecast error by 27%. Nevertheless, complexity remains popular among forecasters and clients at the expense of accuracy.

Why do forecasters avoid simplicity?

One reason is that if the method is intuitive, reasonable, and simple, would-be clients might prefer to do their own forecasting. Another reason is that complexity is often persuasive. We seem to value complexity even when it does not provide material benefits.

Simplicity wins

The simple approach executed well usually leads to better outcomes. Trying to sound interesting by adding unnecessary complexity might impress a client in the short-term, but with history being our guide, mostly dilutes the quality of the decisions and ultimate outcomes.

According to Morgan Housel investing is a negative art. Your success has more to do with avoiding the basic mistakes than outsmarting the market. Research shows that a tennis game is not won by the player who hits the most winners. It is won by the player who makes the least mistakes. In golf your handicap is also explained by how few mistakes you make, not by the odd, glorious shot you pulled off.

Having a diversified portfolio that you can stick to will not only reward you financially in the long-term, but it will also free up your headspace to focus on other areas of your life that need your attention.

The above article was written by Marius Kilian.

Sources:

* Inside the whimsical, but surprisingly dark world of Rube Goldberg machines”, Brendan O’Connor , 2015.

* “The Story Behind Rube Goldberg’s Complicated Contraptions”, Emily Wilson, Smithsonian Magazine, 2018.

* “Occam’s Razor: Problem Solving Principle to Create Simple Solutions”, Vinita Bansal, www.techtello.com.

* “Simple versus complex forecasting: The evidence”, K.C. Green, J.S. Armstrong, Journal of Business Research, Volume 68, Issue 8, Aug 2015.